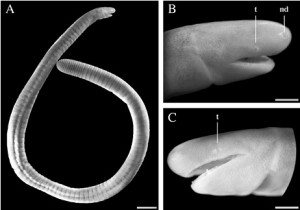

Three new caecilians in the Ichthyophis genus were recently discovered in north-east Indoa. Photo courtesy of The Hindi Newspaper.

In October, a team of researchers led by Associate Professor S.D. Biju from Delhi University, discovered three new caecilian species in Manipur and Nagaland in north-east India. The latest finds increases the number of caecilian species inthe region to nine.

The new species were reported in Zootaxa 2267: 26-42 (19 Oct. 2009) – See Kamei, Rachunliu G. (India), Wilkinson, Mark (UK), Gower, David J. (UK) & Biju, S. D. (India). Three new species of striped Ichthyophis (Amphibia: Gymnophiona: Ichthyophiidae) from the northeast Indian states of Manipur and Nagaland.

An abtract from the article can be found on the Zootaxa web site.

You must be logged in to post a comment.